Methodological problems using Mexico City's pollution data

Jan 11, 2017

Pollution in Mexico City has been a problem for decades. I remember my childhood in the early 1990s as a time of always-grey skies, cheap leaded petrol, and almost unbelievable tales of birds falling dead from the sky. In 1992, Mexico City earned the dubious distinction of the most polluted city on the planet. Many inhabitants of the city were outraged1.

Nowadays the skies are mostly blue and the situation is much improved, which is a real achievement considering the rather inauspicious location of Mexico City in a closed valley more than 2 km above sea level2. This improvement was no coincidence. Tough actions followed the worst years of the pollution crisis, including closing down an oil refinery, moving certain factories outside the city and forcing all cars to install catalytic converters and do stringent twice-yearly emission controls.

However, the most forward-looking reaction was perhaps the creation of a city-wide pollution monitoring system in 1986, which is now known as SIMAT. The system is acknowledged as a big success and is widely used. For one, if the pollution levels reach a certain level on a given day, restrictions on car circulation are imposed for the following day. Many people in Mexico City check the pollution levels more frequently than the weather forecast3.

While the raw pollution data is generally regarded as accurate and reliable, it has some quirks:

- Pollution monitoring stations have been moved many times and the number of stations has constantly fluctuated.

- Not all pollutants are measured at every station.

- Stations are regularly taken offline for maintenance.

All of the above means that many (most?) users of Mexico City’s pollution data use it incorrectly including the Mexico City and the Mexican federal governments. This blog post documents a couple of bad examples that show what I think are the main incorrect uses of the data and hopefully helps others to use it better.

Statistically weak statistics

An intergovernmental working group known as the Comisión Ambiental de la Megalópolis (the Environmental Commission for the Megalopolis) issues environmental alerts based on the maximum pollution level in the city. This is statistically suspect: the more stations that are online, the more likely that a local pollution spike will be detected and an environmental alert will be issued. In turn, this creates a perverse incentive for the government to reduce the number of pollution monitoring stations and to locate them away from polluted areas.

For instance, the station in Xalostoc (an industrial area in the Northeast of the metropolitan area) is often the most polluted in the city. If this station is (temporarily) offline, the chances of a pollution alert being declared decrease substantially. I am certain that if more stations were integrated into the system, particularly in other industrial areas such as Cuautitlán Izcalli, Iztapalapa, or the neighbouring Toluca or Mezquital valleys (which are also part of the megalopolis), it would cause the number of pollution alerts to increase.

For another example of statistically weak statistics, consider the pretty mosaics showing the maximum pollutant data for every day during the past years. They also use only the maximum and fail to take into account the general increase in the number of stations throughout the years.

Not dealing correctly with holes in the data

Raw pollutant levels are hard to grasp for non-specialists. Thus, the government of Mexico (like most other governments) has defined a pollution index called IMECA. Its value is calculated independently for every pollutant (CO, CO2, NO2, ozone, PM10, PM2.5, etc.), but the only number that is easily available and widely broadcast to the population is the maximum for all pollutants per station4.

When you consider this issue together with the fact that not all stations measure all pollutants, another problem becomes apparent: the IMECA value for each station is only really a lower bound (as opposed to its actual but unknown value) and these values cannot be interpolated. And yet, they are directly interpolated by most services, including the otherwise great Hoyo de Smog and the Netatmo app. This is a completely wrong way to provide pollution data at every location5.

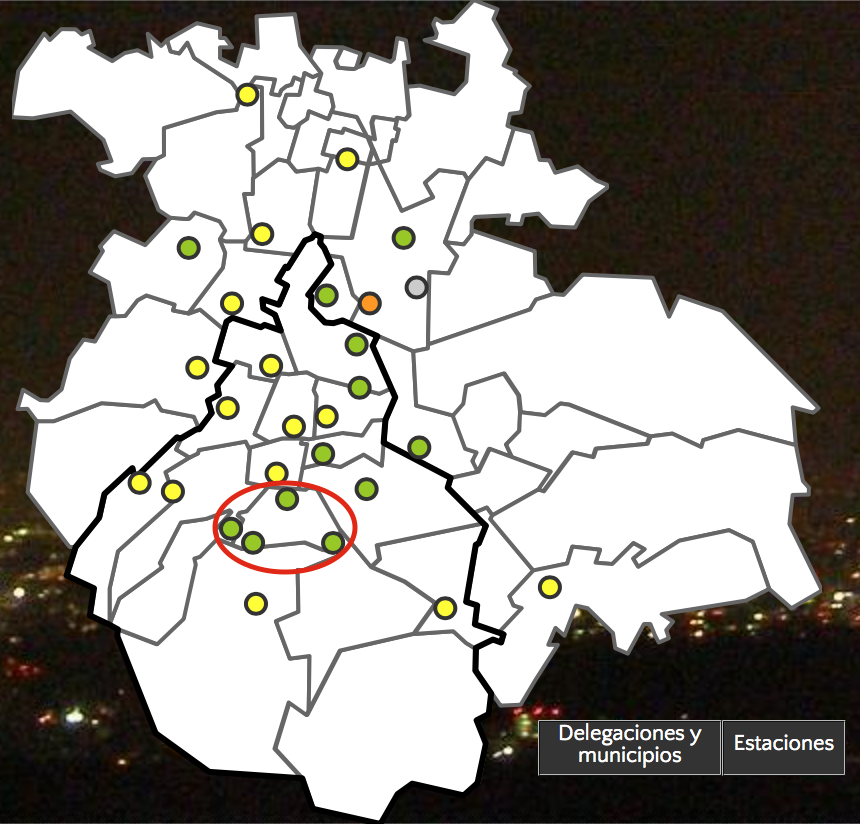

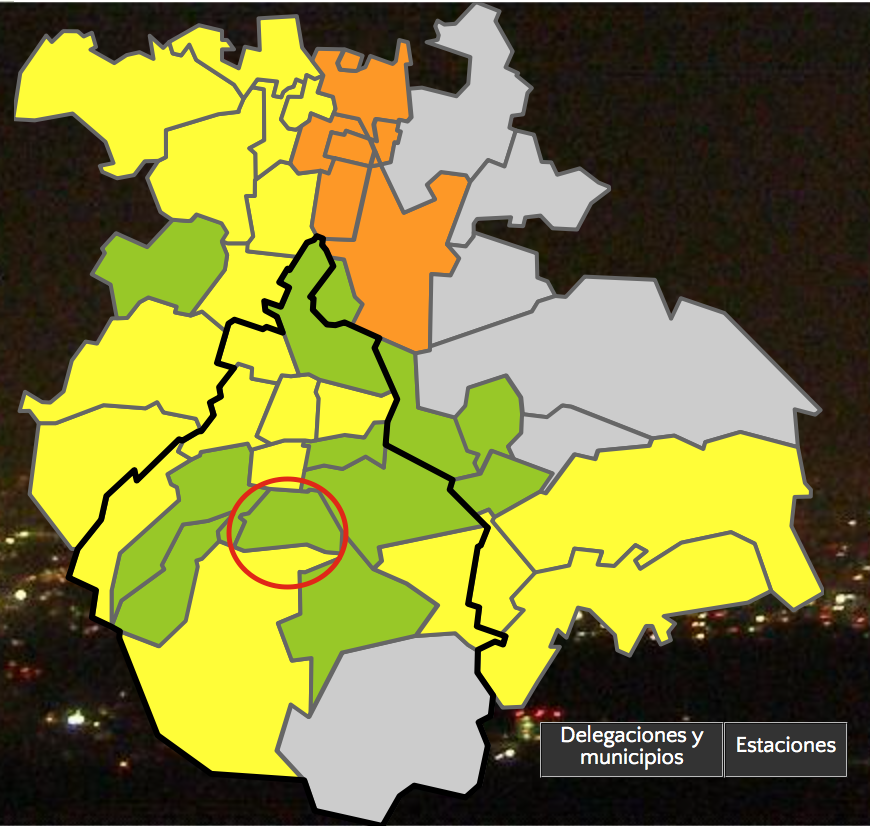

As another bad example, consider the maps shown in SIMAT’s website. Apparently, my home borough of Coyoacán (circled in red) is cleaner than the surrounding area, right? In reality, the monitoring stations in the borough do not measure PM10, which is the main pollutant in these cold winter days6. This is doubly misleading in the borough/municipality view shown on the right where (again) boroughs/municipalities with fewer stations and measuring fewer pollutants are generally shown as cleaner.

Perhaps I’ll end up creating my own real-time pollution map someday. That would be a nice small project.

Appendix: getting the data

-

but the cynical nature of chilangos made more than a few wear it with pride… ↩

-

No other megacity is in a similarly difficult location. ↩

-

which is perhaps not a surprise considering the predictably mild weather of Mexico City ↩

-

which is another case of statistically weak statistics… ↩

-

A still-simple-but-much-better solution: interpolate IMECA values per pollutant, then use the maximum everywhere. ↩

-

due to thermal inversions trapping the pollution in the valley ↩